| From Kenneth Snelson to R. Motro, published in November 1990, International

Journal of Space Structures |

|||

| R. Motro International Journal of Space Structures Space Structures Research Centre Department of Civil Engineering University of Surrey, Guildford Surrey GU2 5XH Dear Mr. Motro: I regret it has taken me so long to respond to your letter about the special issue of Space Structure dedicated to tensegrity. As you probably know, I am not an engineer but an artist so I don't really feel qualified to write for an engineering journal. Nonetheless I know something about this particular form of structure from making so many sculptures over the years which use the principle which I prefer to call floating compression. I have long been troubled that most people who have heard of "tensegrity" have been led to believe that the structure was a Bucky Fuller invention, which it was not. Of course, we are now in the year 1990 and not 1948 so all of this fades into the dim footnotes of history. There is a line somewhere in a theater piece which goes, "But that was long ago in another land -- and besides, the wench is dead." Whenever an inventor defends his authorship the issue invariably turns out to be important only to the author himself, to others it is trivia. Maybe you're acquainted with the tale of Buckminster Fuller and me, but I'd like, somehow, to set the record straight, especially because Mr. Fuller, during his long and impressive career, was strong on publicity and, for his own purposes, successfully led the public to believe tensegrity was his discovery. He spoke and wrote about it in such a way as to confuse the issue even though he never, in so many words, claimed to have been its inventor. He talked about it publicly as "my tensegrity" as he also spoke of "my octet truss". But since he rarely accredited anyone else for anything, none of this is all that surprising. What Bucky did, however, was to coin the word tensegrity as he did octet truss and geodesic dome, dymaxion, etc., a powerful strategy for appropriating an idea. If it's his name, isn't it his idea? As many new ideas do, the "tensegrity" discovery resulted in a way from play; in this case, play aimed at making mobile sculptures. A second-year art student at the University of Oregon in 1948, I took a summer off to attend a session in North Carolina at Black Mountain College because I had been excited by what I had read about the Bauhaus. The attraction at Black Mountain was the Bauhaus master himself, the painter Josef Albers who had taught at the German school and immigrated to the U.S. in 1933 to join the faculty of that tiny liberal arts college (fifty students that summer) in the Blue Mountains of North Carolina, fifteen miles from Asheville. Buckminster Fuller, unknown to most of us in those early days, turned up two weeks into the session, a substitute for a professor of architecture who canceled a week before the summer began. Josef Albers asked me to assist the new faculty member in assembling his assortment of geometric models for his evening lecture to the college. There was no such thing as a tensegrity or discontinuous compression structure in his collection, only an early, great circle, version of his geodesic dome. Albers picked me to help because I had shown special ability in his three-dimensional design class. During his lecture that evening Professor Fuller mesmerized us all with his ranging futurist ideas. As the summer quickly went by with most of the small school monitoring Fuller's classes I began to think I should try something three-dimensional rather than painting. Albers counseled me that I demonstrated talent for sculpture. But, more importantly, I had already become the first in a trail of students from colleges and universities who, over the years, were to become electrified "Fullerites". He had that cult-master's kind of charisma. I blush for it now, but it was true. We were young and looking for great issues and he claimed to encompass them all.

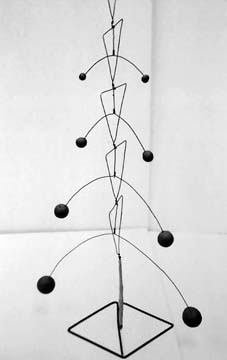

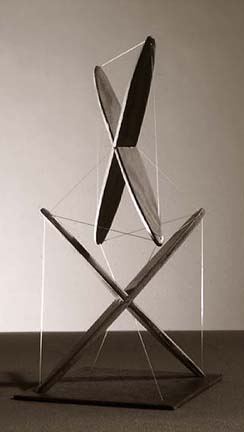

It was the effort to make the pieces move which resulted in their spinal-column, modular, property. If I pushed on them lightly or blew on them, they swayed gently in a snake-like fashion. In photo #2 one can see module-to-module sling tension members replacing the wire hinges connecting the modules shown in photo #1. I thought of these threads as adding a note of mystery, causing the connections to be more or less invisible, at least as invisible as marionette strings; an Indian rope trick. One step leading to the next, I saw that I could make the structure even more mysterious by tying off the movement altogether, replacing the clay weights with additional tension lines to stabilize the modules one to another, which I did, making "X", kite-like modules out of plywood. Thus, while forfeiting mobility, I managed to gain something even more exotic, solid elements fixed in space, one-to-another, held together only by tension members. I was quite amazed at what I had done. Photo #3 Still confused about my purposes and direction in school, I enrolled for engineering that winter ('48-'49) at Oregon State College. The classes depressed me even further. I hated it and did very poorly. I corresponded with Bucky and I told about my dilemma and also sent photos of the sequence of small sculptures. He must have understood from the letter how confused and depressed I was at school for he suggested I return for another Black Mountain Summer Session.

Next day he said he had given a lot of thought to my "X-column" structure and had determined that the configuration was wrong. Rather than the X-module for compression members, they should be shaped like the central angles of a tetrahedron, that is like spokes radiating from the gravitational center, to the vertices of a tetrahedron. Of course the irony was that I had already used that tetrahedral form in my moving sculpture #2, and rejected it in favor of the kite-like X modules because they permitted growth along all three axes, a true space-filling system, rather than only along a single linear axis. Those were not yet the years when students easily contradicted their elders, let alone their professors. Next day I went into town and purchased metal telescoping curtain rods in order to build the "correct" structure for Bucky. I felt a little wistful but not at all suspicious of his motive as he had his picture taken, triumphantly holding the new structure I had built. The rest of the story is one of numerous photographs and statements in print, grand claims in magazine articles and public presentations. In Time magazine he declared that, with "his" tensegrity, he could now span the Grand Canyon. He also described it as a structure which grows stronger the taller you build it -- whatever that may have meant. The absorption process began early, even though Bucky penned the following in a letter to me dated December 22, 1949:

Bucky's warm and uplifting letter arrived about six months after I first showed him my small sculpture. In that it was dated three days before Christmas, I suppose he was in a festive, generous, mood. A year later, January 1951 he published a picture of the structure in Architectural Forum magazine and, surprisingly, I was not mentioned. When I posed the question some years later why he accredited me, as he said, in his public lectures and never in print, he replied, "Ken, old man, you can afford to remain anonymous for a while." Finally, in 1959 I learned that Fuller was to have a show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and included in it was to be a thirty-feet high tensegrity "mast". Calling it a mast seemed especially obtuse, but he regarded himself as a man of the sea. With some persistence and with the lucky aid of Bucky's assistant I was able to get word to Arthur Drexler, curator at the Museum, about my part in tensegrity. This forced Bucky's hand. At last, my credit for tensegrity found its way into the public record. One of the ironies of this not-too-unusual tale in the history of teacher-student relationships, is that by Bucky's transposing my original "X" module into the central-angles-of-the-tetrahedron shape to rationalize calling it his own, he managed successfully to put under wraps my original form, the highly adaptable X form. He could not have lived with himself with the blatant theft of my original system, of course, and besides, he had denounced it as the "wrong" form. As a result, none of the many students in schools where he lectured ever got to see it. In those years, any number of students labored to constructed their own "masts", but all were built using the tetrahedral form. That moment of recognition at the Museum of Modern Art in November 1959, transitory as it was, was quite fortifying and enabled me to once again pick up my absorbing interest in this kind of structure with the feeling that now I was free and on my own. Especially I picked up where I had left off with the neglected X-module which was left unnoticed for an entire decade. I no longer felt anonymous. As I said earlier, this is but a footnote to a storm in a teapot. I have continued to make sculptures which now stand in public sites in many places. Sorry there are none in England or France. The ghost of Bucky Fuller continues to muddy the water in regard to "tensegrity". I tell myself often that, since I know where the ideas came from, that ought to be enough. As I see it, this type of structure, at least in its purest form is not likely to prove highly efficient or utilitarian. As the engineer Mario Salvadori put it to me many years ago, "The moment you tell me that the compression members reside interior of the tension system, I can tell you I can build a better beam than you can." He was speaking metaphorically about this type of structure in general, of course. Over the years I've seen numbers of fanciful plans proposed by architects which have yet to convince me there is any advantage to using tensegrity over other methods of design. Usually the philosophy is akin to turning an antique coffee-grinder into the base for a lamp: it's there, so why not find a way to put it to some use. No, I see the richness of the floating compression principle to lie in the way I've used it from the beginning, for no other purpose than to unveil the exquisite beauty of structure itself. Consciously or unconsciously we respond to the many aspects of order in nature. For me, these studies in forces are a rich source for an art which celebrates the aesthetic of structure, of physical forces at work; force-diagrams in three-dimensional space, as I describe them. Whether or not you are able to use this narrative about the beginnings of tensegrity, I wish you the very best with your special issue on the subject. Sincerely, Kenneth Snelson |